Design for Succession: Infrastructure That Survives You

Companies die. Projects end. Good infrastructure survives both. Here's how to design systems that communities can take over when you disappear.

When Pebble smartwatches shut down, the devices didn't become bricks. The community created Rebble—infrastructure to keep everything working after the company disappeared. Servers, APIs, app store, firmware updates. The succession worked because Pebble's architecture made it possible to fork.

This isn't unique. HomeAssistant, LibreOffice, Firefox—all examples of infrastructure that survived organizational collapse or pivoted to community stewardship. The pattern: when commercial entities exit, communities take custody. The variable: whether the infrastructure was designed to survive that handoff.

Most systems aren't. They assume the original operator will exist forever. That assumption breaks, and users are left with dead weight.

The Succession Question

Do you build assuming you'll maintain this forever, or do you design for the reality that someone else will need to run it when you're gone?

The latter approach changes how you make architectural decisions. Not radically—just intentionally. You document differently. You choose data formats differently. You expose APIs differently. You think about what happens when the original operator disappears.

This is Build Once, Use Forever applied to organizational mortality. The capability should persist beyond any single maintainer.

Succession-Friendly Infrastructure

Here's what makes infrastructure easy to fork and maintain:

Open data formats

- Use standard formats (JSON, SQLite, Markdown) not proprietary schemas

- Document the data model explicitly

- Make exports trivial, imports possible

- No vendor lock-in at the data layer

Documented APIs

- Public API documentation, even for internal calls

- Versioning strategy that doesn't break on updates

- Clear authentication patterns

- Endpoints that make sense without insider knowledge

Runnable without the mothership

- Self-hosting should work without phoning home

- Core functionality doesn't depend on external services you control

- Graceful degradation when cloud pieces disappear

- Local-first where possible

Explicit dependencies

- List every external service, library, tool required

- Pin versions or document compatibility ranges

- Make it clear what breaks if a dependency vanishes

- Prefer fewer dependencies over convenient ones

Forkable codebase

- Open source license (obviously)

- Readable code with explanatory comments

- Setup instructions that work for someone who's never seen this before

- No magic configuration that only the original team knows

Succession-Hostile Patterns

What makes infrastructure hard to take over:

Closed protocols

- Proprietary communication formats

- Undocumented API contracts

- Authentication tied to specific provider

- Data schemas that only make sense to insiders

Cloud dependency

- Core features require your specific cloud account

- No path to self-hosting

- Hard-coded service endpoints

- Phone-home requirements that can't be disabled

Insider knowledge requirement

- Setup requires tribal knowledge

- Configuration files with magic values

- Build processes that only work on the original team's machines

- No documentation because "we all know how this works"

Legal barriers

- Restrictive licenses

- Patent encumbrance

- Terms of service that prohibit forking

- Trademarks that block community continuation

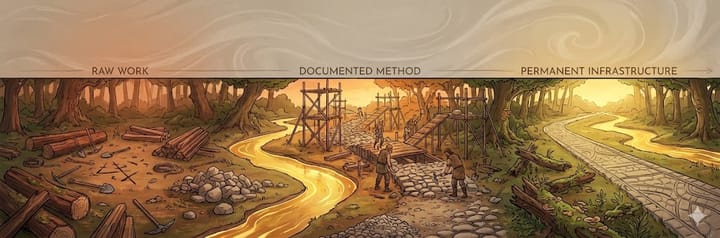

The Stewardship Method

Here's the practical workflow for designing succession-friendly infrastructure:

1. Document setup from scratch Write installation instructions assuming someone who's never seen this project before. Test them on a fresh machine. If it requires more than five external accounts or services, simplify.

2. Use standard formats everywhere Default to the most boring, widely-supported data format that works. JSON over custom binary. SQLite over proprietary database. Markdown over rich text. Future maintainers thank you.

3. Expose everything via API Even internal functionality. If your code uses it, document it. Make the API consistent and predictable. Version it. This creates forkability.

4. Make self-hosting default Cloud features are fine. But the core should run entirely on one machine without external dependencies. Add cloud later as enhancement, not requirement.

5. Write the handoff docs now Create a "How to Take Over This Project" document. What services need migration? What credentials need replacement? What's the first thing to fix when the original team is gone? Write it while you still remember.

Coherence Through Succession Design

This is Field Stewardship in practice. You're not just building for today's users—you're building for the people who'll maintain this after you exit.

It's also Alignment over Force. Instead of forcing future maintainers to reverse-engineer your system, you position the architecture so succession is natural. The structure enables the handoff.

Companies will fail. Projects will end. Maintainers will move on. These aren't edge cases—they're certainties. Designing for succession doesn't mean planning to quit. It means building infrastructure that becomes a permanent capability, independent of who operates it.

The Reusable Pattern

Before shipping infrastructure, ask:

- Can someone else run this if I disappear tomorrow?

- Are the data formats standard and documented?

- Does self-hosting work without my accounts/services?

- Is there a clear handoff path for new maintainers?

- Would a community fork be technically possible?

If the answer to any of these is no, you've built something fragile. It might work great today, but it's got an expiration date tied to your organization's lifespan.

Build for succession. Make forking easy. Document the handoff. Use standards. Enable self-hosting.

Your infrastructure will outlive you. Design it that way from the start.