The Consent You Owe Now

Institutions conflate originating consent with joining consent constantly. And the conflation isn't innocent.

The American Revolution wasn't a dispute about England's right to govern. The colonists never argued that the original compact—the settlement of the colonies under Crown authority—was illegitimate. They argued something more dangerous: that doesn't matter anymore.

What mattered was current performance. Taxation without representation. Quartering of troops. Dissolved legislatures. The colonists were conducting a real-time evaluation of British rule and finding it wanting. England kept pointing to founding authority. The colonists kept asking about present conduct.

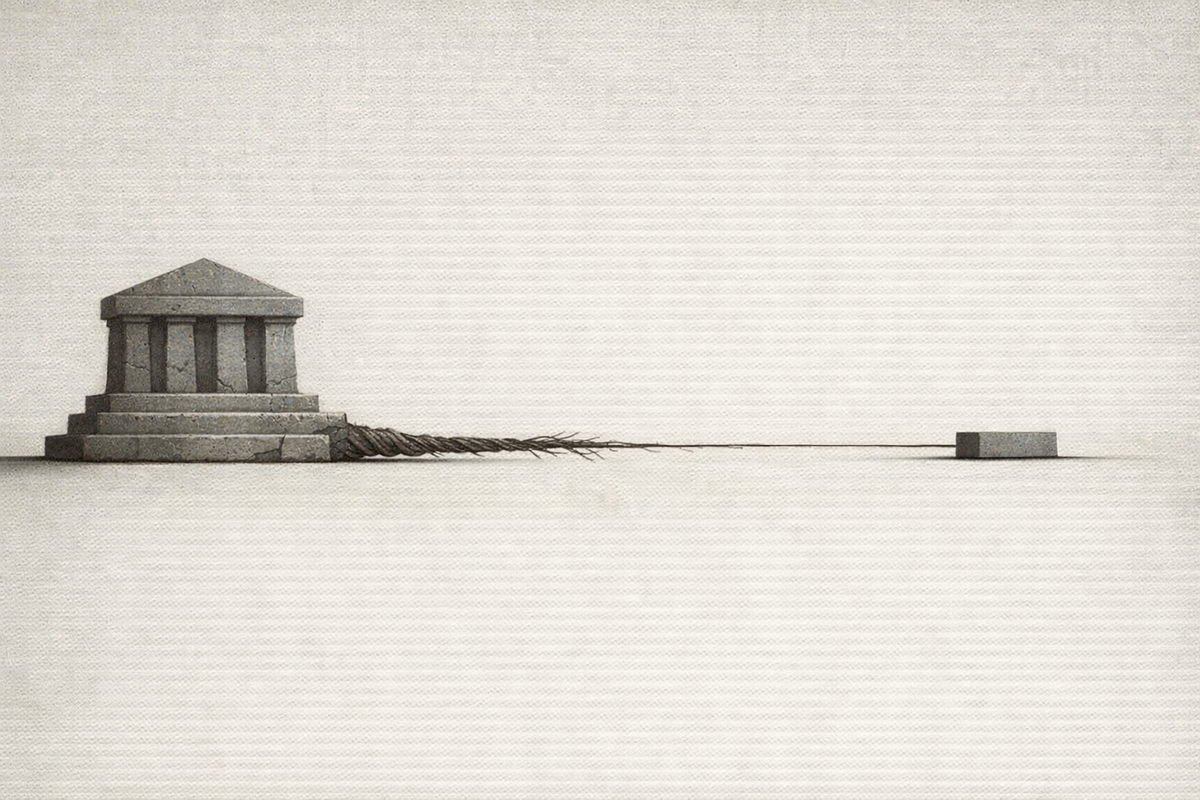

This is the distinction between originating consent—the initial institutionalization of authority, the moment when power becomes legitimate—and joining consent, the ongoing evaluation of whether that authority still merits allegiance.

Institutions conflate these constantly. And the conflation isn't innocent.

When a company facing criticism points to its founding mission, it's performing a substitution. When a political party invokes its historical achievements to deflect from current failures, same move. When "we've always done it this way" becomes an answer to "should we still do it this way?"—that's originating consent deployed to avoid joining consent questions.

The pattern: founding stories become shields against accountability.

"We were created to do X" doesn't answer "are you doing X well now?" But the rhetorical force of origin stories—their sacred status, their connection to identity and continuity—makes them feel like answers. The Constitution gets invoked not as a framework for evaluation but as an override against it. Mission statements become talismans rather than standards.

This is how legitimacy gets laundered. Past achievements purchase present immunity. The institution borrows authority from its founding and never pays it back through performance.

Every legitimacy crisis replays this pattern. The institution points backward; the critics point at now. The institution speaks of founding; the critics speak of performance. And somewhere in the gap between those conversations, allegiance erodes.

This doesn't mean founding principles are irrelevant. They establish identity, set standards, create the criteria by which current performance should be judged. The Constitution matters—as a measuring stick, not a shield.

The distinction isn't between reverence and cynicism. It's between two different questions that sound similar but aren't:

- "What authority were you granted?" (originating)

- "What have you done with it?" (joining)

The detection capability is simple: when an institution invokes its founders, its mission, its original purpose—ask whether that's an answer or an evasion. Are they using their origin story to meet the standard or to avoid the question?

Legitimacy is borrowed from the past but owed to the present. The American revolutionaries understood this. So does anyone who's ever asked an institution to stop telling them what it was created to do and start explaining what it's doing now.

The consent that matters isn't the one given at founding. It's the one you owe today.

Sources: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Locke via Rawls on political legitimacy